Towards the end of last year, when it looked like inflation was tamed and interest rates were set to fall, we saw markets lift. Santa did not just rally – he threw some parties. In the UK it was a modest affair – the FTSE 100 rose 5.4% across November and December. In the US there was a little more in the punch bowl – the S&P 500 climbed 13.1%.

But we are now officially into spring and still to see those promised interest rate cuts. China continues its struggles to emerge from recession, and there are serious concerns about the growth outlook in Europe. So why are markets still looking buoyant? Europe’s TOPIX index is up over 14% this year, the S&P is up a further 8%, and the Nikkei is up 21%. The FTSE, an outlier, is down – but only by 1%.

If you are a global investor, this would seem to be a good environment in which to take profits. There are good reasons for not doing so – and for believing markets can go higher.

At the end of January, $6trn was sitting in money market funds. That is a lot of cash on the sidelines. Investors have parked it there because, thanks to sharply higher interest rates, returns look so much more attractive than they have for decades.

But this could change. Many may have to switch into equities to generate a real return if rates fall and inflation settles in mid-single-digit figures.

Could that happen? The Office for Budget Responsibility may be forecasting 2% inflation soon in the UK, but inflation is like a moorland fire – hard to extinguish and likely to re-erupt as soon as you turn your back. Highly indebted governments have an incentive not to bring inflation down too far, too fast. Inflating away the debt may be their best way of cutting it.

Cash savers may come to rue the opportunity cost of sitting on the sidelines if economic confidence grows. And there are several reasons to think it might.

Half the world is going to the polls this year. At the risk of sounding like a cynic, that enhances the likelihood of fiscal stimulus of some kind. We saw it in the Budget in the UK, with the cut in National Insurance. In some regions the narrative is shifting from when the recession will come to what type of boom we will experience – disinflationary or inflationary.

Those fearing recession should look to full employment in most regions and leverage in the system. In a way, the ‘mini’ banking crisis last year demonstrated that you can have significant idiosyncratic events without contagion. In aggregate, household and corporate debt levels do not look stretched across the Atlantic or elsewhere, and the mainstream financial sector around the globe is well capitalised.

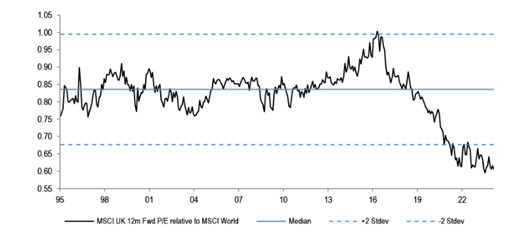

Nor do equity valuations look stretched. There is surely headroom for most markets to rise further. Apart from in the US, markets represent reasonable historical value and even there they are not expensive if you consider an equally weighted S&P 500 index. Emerging markets, Japan (notwithstanding recent rises) and the UK look remarkably cheap. The chart below shows just how low the UK market has sunk relative to global markets since 2016.

MSCI UK 12 month forward P/E relative to MSCI World

Sources: Datastream and Artemis

When, as happened recently, Barclays can go up 12% in one day on its results, yield nearly 5% and still be trading on a significant discount to book value, surely investors will start waking up to the risk they are taking in not participating.

Management teams are certainly aware of the opportunities. Across the UK, companies are using profits to buy themselves. Thirty companies on the FTSE All-Share index saw their number of shares fall by 5% or more in 2023 – largely as a result of share buybacks. Over three years, 27 companies have bought back 10% or more of their shares. It is happening with all sizes of company. Last year around one in eight listed UK smaller companies bought back shares. None of us here can remember anything like it.

And if it is not managements buying their shares cheaply – it is private equity and competitors. The Artemis UK Smaller Companies fund has seen a dozen of its stocks subject to takeover activity in the past two years, at an average premium of 48%.

One area of concern is private markets. A lot of private market deals in recent times were based on reference value rather than any view of sustainable economics – or they were high growth/high risk tech deals that were fine when interest rates and inflation were low. It is a very different picture now. This is an opaque part of the market, and I think many issues are yet to emerge.

But listed markets look reasonably healthy. Covid was an opportunity for those companies that had got themselves trapped into paying too much in dividends to have a reset. High interest rates have flushed out many tech companies that were priced on unrealistic expectations of plenty, and in cyclical areas we have seen highly leveraged companies fold. The feeling is that those that are still standing have less competition and have demonstrated their strength.

When you view it like that, it is not surprising that markets have been so resilient. The one big surprise in there is that the FTSE has not climbed in line with other markets. Will that change? Catalysts are hard to predict, but market swings, when they come, can be sharp and quick. If the FTSE bounces to something like a reasonable valuation any time soon then 5% in a money market fund will look very disappointing indeed.

Paras Anand is chief investment officer of Artemis. The views expressed above should not be taken as investment advice.