Money market funds have had a barnstorming past year but their run of popularity could be coming to an end, according to Kevin Thozet, a member of the investment committee at Carmignac.

Their return to the mainstream has been sharp and is far from abating. Over the past 12 months, investors have added a net £2.6bn to the IA Short Term Money Market sector, according to data from the Investment Association (IA).

Savers ploughed money in at the start of the year, adding £1.1bn in January 2024 alone, showing they remain a popular option in the current climate. There has also been a total net £686m added to the IA Standard Money Market sector over this time.

Thozet said investors have been lured in by the “prospect of handsome returns”. Money market funds invest in cash and cash-like instruments such as floating-rate notes, where yields are closely tied to interest rates.

The other reason they have proven popular is due to fears of a repeat of 2022, when equity and bond prices fell in tandem.

“This was good news for sovereign issuers. Government bonds targeted to retail investors proved highly successful in Europe and the US Treasury was able to finance its deficit through short-dated paper,” he said.

“It was a boon for investors, too, as money markets delivered attractive returns in 2022 and the first half of 2023.”

However, he warned that central banks are standing pat on interest rates and likely to start pivoting towards an interest rate cutting cycle this year while a growing number of these government bonds will soon reach maturity.

“Today, anyone who invests in a money market fund or short-term deposits with an attractive nominal interest rate should realise that the rate will most likely be lower when the time comes to roll over such investment,” said Thozet.

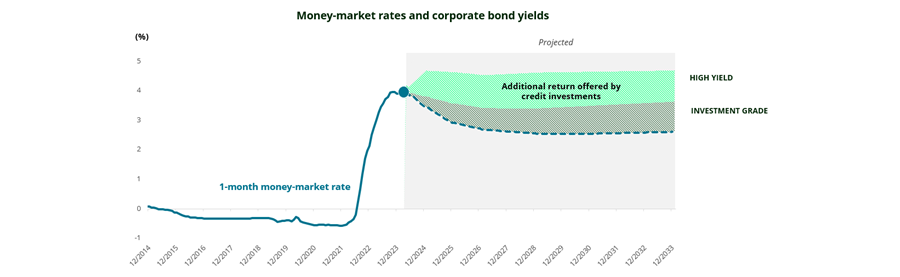

For investors in money market funds, the managers take care of this for them. As such, returns from money market funds are likely to fall. This is represented in the chart below by the dotted blue line.

Source: Carmignac

To get the best returns, investors should consider moving up the credit spectrum, Thozet said. The green and grey areas in the chart above show the additional return on offer from high yield and investment grade bonds.

“Or, put another way, these areas indicate the ‘opportunity cost’ to investors if they leave their savings in the money market or are slow to change their asset allocation. This opportunity cost sits at 1 percentage point to 2 percentage points per year – hardly a negligible sum,” he explained.

For example, someone with £50,000 could invest for two years in a money market fund paying 3%, which would net £3,000 at the end of the 24 months.

According to the chart, however, if an investor puts their cash in credit markets, they’ll get a £3,800 capital gain from investment grade bonds or a £4,700 return from high-yield bonds, based on current interest rates expectations.

“It will be key to have a good grasp of investor behaviour – influenced heavily by central bank decisions – if only for the highly speculative nature of such behaviour. To paraphrase Schumpeter: Interest rates are at the heart of any financial transaction or calculation,” Thozet concluded.