It has been a disappointing time for commodity investors who were swept up in the idea of a supercycle.

In 2021 and 2022 commodities soared. The Bloomberg Commodity index was up 28.2% in the first year, before rocketing a further 30.8% in the second.

There were myriad reasons for this, including oil price shocks due to the war in Ukraine and Covid-related supply chain issues. Hopes of a big drive towards net-zero emissions and a ramp up of fiscal spending following the pandemic also undoubtedly played a part in the renaissance.

Yet commodities have been much slower since. Indeed, the same index lost 13.1% last year and is down a further 2% so far in 2024.

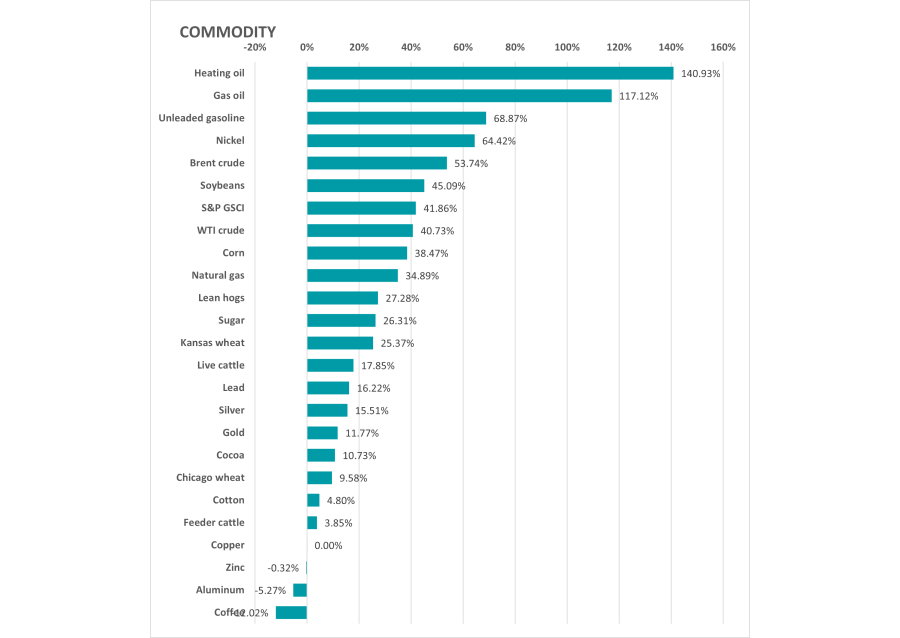

The below tables highlight the disparity even further. In 2022, most commodities rose, with huge gains for the likes of Brent crude, as well as heating and gas oil.

Performance of commodities in 2022

Source: FinXL

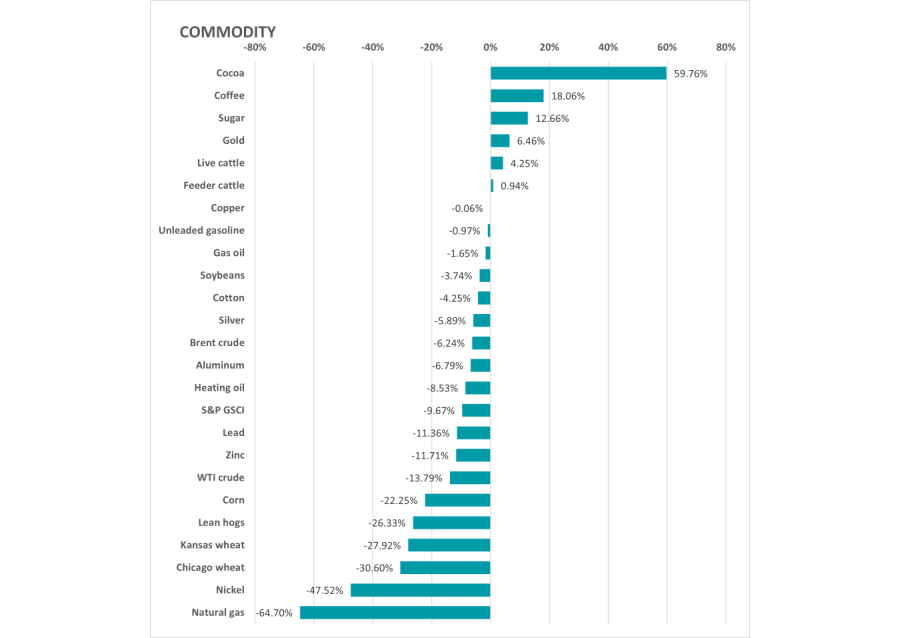

In the following 12 months, there were few winners, however, with some commodities such as natural gas down by almost two thirds, while nickel dropped 47.5%.

Performance of commodities in 2023

Source: FinXL

There have been bright spots. Gold did not perform spectacularly in 2021, but was one of the few commodities to rise last year.

David Waugh, a quantitative analyst in Neuberger Berman’s multi-asset team, said commodities peaked in March 2022, immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“A confluence of factors has dampened demand [since then] and altered market dynamics. Key among these is the prevailing interest rate uncertainty, which has fostered a climate of risk aversion, leading to massive destocking efforts by businesses as they try to reduce the cost of locking up capital in raw material inventory during a high rate environment,” he said.

The most dramatic reversal of fortunes has perhaps been oil, which rocketed after Covid. Here, Waugh noted western governments have overlooked sanctions in some regions (such as Iran) and released reserves to flood the market.

“Shale production in the US has surprised to the upside, due to a notable one-time boost from drilled-but-uncompleted wells, which were held up by supply chain issues following Covid,” he said.

Peter Sleep, senior investment manager at 7IM, added: “The recession in construction, particularly in China, has caused a fall in demand for construction materials such as steel, used in reinforced concrete, and copper which is used in plumbing and wiring.”

The idea of a commodity supercycle seems to have been overstated, Sleep noted, suggesting the market is in a regular cycle where things are cheap and unprofitable for a long time so no new money gets invested in production, while some producers quit the market altogether.

“Then there is an uptick in demand and the industry cannot increase production quickly enough so prices rise. Suddenly, all the remaining producers are very profitable,” he said.

“Demand goes up a bit more and the profitable producers expand production to meet new demand and to cash in on the high levels of profitability. Production expands for a period and times are good. Then demand drops slightly or production expands too much and all of a sudden prices and profits start to drop.”

After this, a price war develops and soon profits disappear, he said. But this is not a commodity phenomenon – it happens across the market, whether it be for semiconductors, construction materials or technology.

Within commodities, the length of this can vary. Some have short cycles such as grains – where farmers can switch reasonably quickly from one crop to another – while others take longer, such as metals, which take years to get out of the ground.

Which commodities will rise again?

Waugh said metals could emerge as the most promising sector, as the green energy transition is driving a “process of metallisation and electrification of the economy”, particular in the electric vehicle (EV) space.

Additionally, “greater geopolitical uncertainty and gradual deglobalization also drives governments around the world to engage in strategic nearshoring and stockpiling of metals,” he said.

“Within metals, we prefer a diversified portfolio across several base metals, while placing a special emphasis on the harder-to-substitute and more challenging-to-recycle metals with cross-cut applications such as copper and aluminium.”

Sleep agreed that copper could be the best commodity in the coming years, but noted if investors are going to buy copper they should only invest a very small proportion of a portfolio.

“Unlike [other] investments, commodities produce no income – rather the reverse, you will have to pay for handling charges, shipping charges and storage,” he said.

For the more adventurous, lithium is another option, although he suggested that the metal “seems to be in late cycle”.

“Too much production and EV battery demand slackening off a bit has sent the price down and some producers are cutting production because they are losing money.

“The price might bounce in the short term, but unlike copper, lithium seems to be relatively abundant worldwide and is not scarce. I would buy lithium instead of having a punt on the Grand National. I would not waste my SIPP or ISA allowance on it.”